No Cultures Left to Appropriate

by Caitlyn Chung ‘20 and Midori Yang ‘19

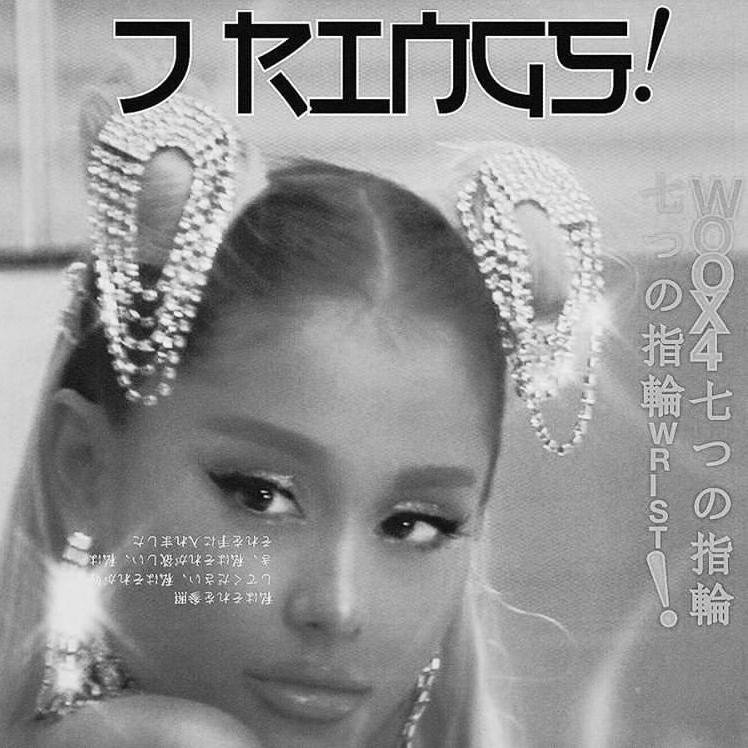

Ariana Grande’s Japanese tattoo has recently gained international attention, but not for positive reasons. The hand tattoo, inspired by her music video titled “7 Rings,” was supposed to be a translation of the song’s title in Japanese. The full Japanese translation is “七つの指輪,” as shown repeatedly in the music video and in promo materials for the song. However, when Ariana got the tattoo, she shortened the phrase to ”七輪” due to the pain of getting the tattoo. Unfortunately, the phrase no longer translates to “seven rings,” but instead, an idiom that means “small Japanese charcoal grill.” Originally, Ariana responded to internet backlash by tweeting that she was “a huge fan of tiny bbq grills” and was fine with the results. However, after conversing with her Japanese tutor and a sympathetic fan on Instagram, she attempted to correct it by getting the missing “指” character inked underneath the original tattoo. The new character was placed in such a way that the new tattoo now says “small Japanese charcoal grill finger.”

To her credit, Ariana Grande has been studying Japanese since 2015 in order to connect with her large Japanese fanbase. Her tutor, Ayumi Furiya, has also come out in support of her decision to learn the fundamentals of the language instead of memorizing “basic phrases” that could be used in response. Furiya has also noted that Ariana has not been able to dive deeply into her Japanese studies because of her time constraints; she only knows the basic phonetic alphabet, hiragana, and therefore had not advanced far enough to begin learning the system of adopted Chinese characters, known as kanji. Regardless, Ariana Grande failed to verify the meaning of 七輪 despite having access to her tutor and even Google Translate (which accurately translates 七輪 to either “tambourine” or “earthen charcoal brazier”).

Ariana’s mistake in itself would not have blown up if it was an isolated incident of mistranslation. Yet, her mistake is one that has been repeated throughout history by many other non-Asians. She is not the first person to get a nonsensical tattoo in an Asian language that she barely knows and has failed to research. Her decision is part of a larger trend in which Asian cultures are decontextualized and commodified for the sake of aesthetics. Whether it’s fashion, pop music, or traditional noodle dishes, the same cultural products that many Asian American children have been bullied for having are now cool and cute trends that every person wants to participate in. Such cultural appropriation comes from a place of privilege and hypocrisy that only white people can truly access: picking and choosing which elements of non-white cultures they want to consume without having to navigate the gauntlet of racism.

Historically, Asians have never been accepted as part of American culture. There is a lingering notion of the “perpetual foreigner” that disallows Asian Americans from entering the Western space without assimilation. Many Asian Americans have their own stories of being denied access to their heritage. Immigrant parents often give their children Anglicized names, pushing their ethnic names aside as middle names or forfeiting them altogether; they regularly refuse to teach their children their native language for fear of bullying and ostracization. These kids grow up trying their best to fit in, asking their moms to pack a more “normal” lunch after getting asked why their cultural food smells weird by non-Asian classmates. From early childhood, they’ve learned that in the public sphere, the whiter, the better. But in the privacy of their homes, they still could not completely escape their cultural heritage. While taught to assimilate, they’re still surrounded by artifacts from their families’ culture. Because many grandparents, and even parents, cannot speak English, many immigrant families need the help of their children in order to survive in the new world (such as helping with taxes, translating documents, or ordering in restaurants). This inability to fully escape from their heritage, while not quite being a part of the larger American population, creates a void of cultural ambiguity where a child may not feel “Asian” or “American.”

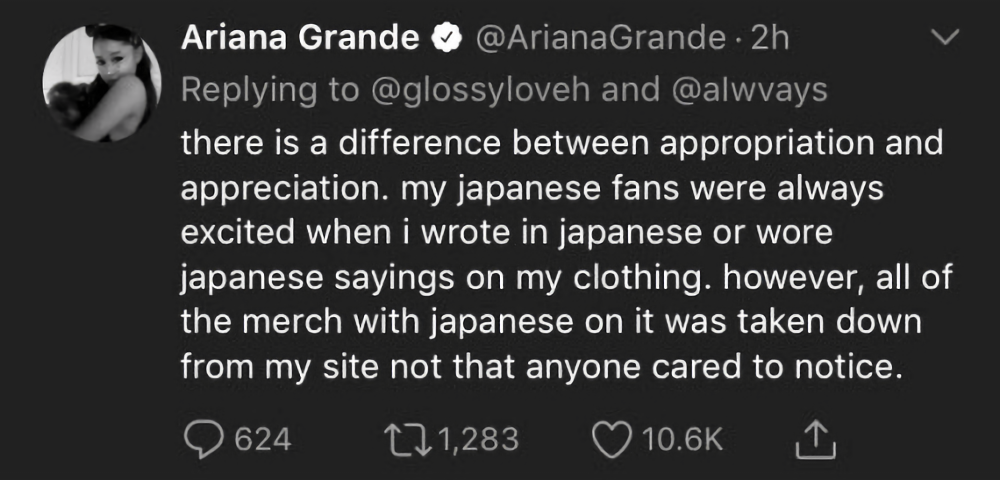

This cultural identity limbo leads Asian Americans to be ostracized by both groups with whom they identify. Asians who have always lived in Asia often discredit the opinions of Asian Americans and their interpretations of Asian culture. Americans then use these arguments to further invalidate our grievances. For example, many of Ariana’s Japanese fans describe the tattoo incident as “funny” and “cute.” In incidents like Hollywood’s Ghost in the Shell (a live-action adaptation of a Japanese animated film featuring a Japanese main character), many Japanese fans, including the director of the original movie, announced their support of Scarlett Johansson in the main role. Their praise stood in direct contrast to the laments of Asian Americans who wished for representation in a major blockbuster film. Our opinions, when voiced against the white population, are often ignored or blatantly mocked as “sensitive” and “reaching” by both Americans and those in Asian countries.

Cultural appropriation like this is decidedly an Asian American issue and not an Asian one. When those living in Asia, who are thought of as more “authentically Asian,” tell Asian Americans that our experiences don’t matter, it further reinforces how we are not “Asian enough” to have a voice in the argument. Japanese people in Japan don’t understand what it feels like to be a minority and to never see yourself reflected in the media around you, a concept that extends to many other immigrant communities. As of 2018, Japan is 98.5% Japanese. Japanese people have never experienced an environment where their culture is not the dominant one and where they are the “other” because of their race. Many fans view gestures of appropriation like Ariana’s as a sign that an outsider is taking interest in their country, and are excited by the prospect (although a fair share of Japanese netizens were also confused by the tattoo). Ariana’s tutor has said, “Japanese is not a common language in the world. It’s not necessary for her to learn Japanese—she just really wants to. I appreciate that. It makes her Japanese fans so happy.” Unfortunately, not all Japanese Americans consider Japan their country, and celebrities’ fleeting fascination with Japan and other Asian cultures in general does nothing but further exotify Asian-ness.

The collective memory of many young Asian Americans today still consists largely of microaggressions and cultural isolation. The Chinese Exclusion Act, Japanese internment camps, the Tydings-McDuffie Act, and many other anti-Asian policies lie not so far in our past. Today, especially with the rise in Korea’s and Japan’s cultural power, Asian culture is now deemed cool enough to become part of the mainstream, ranging from food to fashion to music. But this relatively recent acceptance does not suddenly give white people permission to step into a cultural space that is not theirs. When a pop star like Ariana Grande carelessly treats an Asian language as an accessory, it’s simply playing into a long history of white people appropriating a culture that does not belong to them. Though some forms of acceptance have come through the recent popularization of Asian culture—food in particular—white Americans still hold the power to decide what is accepted into the public sphere. Sushi, banh mi, pad thai, boba, KBBQ, and countless other dishes only make up a small percentage of Asian cultures, but are touted by the white majority as shining beacons of Asian food. This same concept extends to all facets of popular culture, such as anime, music, video games, and many more. And yet, Asian Americans rarely make these choices themselves—we do not get to own our own culture, but white Americans can come and go as they please.

As demonstrated by Ariana and many celebrities before her, it is easy to fall into the trap of appropriating and misrepresenting Asian culture through ignorance. But there is still hope! Non-Asians are not barred from engaging with Asian culture by any means. However, there are respectful ways to do it. What many people are missing from their interpretation of Asian cultures is an understanding of the deeper historical context that surrounds these trends. Like any culture, mainstream Asian culture is just the surface level on decades of culture and counterculture that have evolved and adapted to varying circumstances. Many non-Asians entering Asian culture may feel that they are obligated to constantly apologize, possibly by acknowledging that they are an outsider (“I’m not Asian, but...” or “I didn’t grow up with this culture, but from what I’ve learned…”). But this sentiment does not have to manifest as guilt, and can instead be turned into a desire to learn about all facets of the culture they wish to enter and an effort to engage with its negative aspects as well as the positive—idealizing a culture to the point of ignoring its flaws is still fetishization.

Cultural appropriation in its many forms do not just apply to Asian Americans, but to many other minority groups. Listed below are some resources that are a good starting place to learn about the differences between respectfully engaging in a foreign culture and cultural appropriation:

“The Chun Li Challenge is the Latest Example of Pop Culture Stereotyping Asian Culture” by David Yi for Teen Vogue

“White People Need to Learn How to Appreciate a Different Culture Without Appropriating It” by Alisha Acquaye for Teen Vogue

“The undying trend of cultural appropriation” by Amma Aburam for gal-dem

We hope that you, unlike Ariana, take the time to consider these complicated sociopolitical and cultural histories before you engage with our cultures.